When my oldest daughter was about three years old, I was out for an afternoon with friends and my husband was trying to get her down for a nap. He called me in a panic because our daughter had taken all the removable parts out of our couch and refused to put them back in.

My husband could not even persuade her to give them back to him, much less get her to sleep.

I laughed when my husband told me the story because I could totally see our daughter doing that. I knew then that she had strong tendencies toward manipulating and creating with Loose Parts.

My role as a mother and educator was sparked by my daughter’s creativity and design perspective. I knew then that the more opportunities for discovery I offered her, the more she would grow in creativity and intellectual thinking.

I never imagined that I would end up writing about something that came instinctually into my parenting.

Both my daughters are now grown, but my love for these beautiful ordinary objects has grown and evolved into an educational philosophy that guides my work and beliefs about how children grow and develop.

The Loose Parts educational philosophy is based on the belief that children are innately creative and resourceful. The objects, or Loose Parts, provide opportunities for children to engage in unscripted play which allows them to explore their strengths and abilities.

This type of play is complex and unpredictable, requiring educators’ understanding of theory and research..

In this article, I want to highlight the specific processes and ideas behind the Loose Parts Method.

From an object to an action:

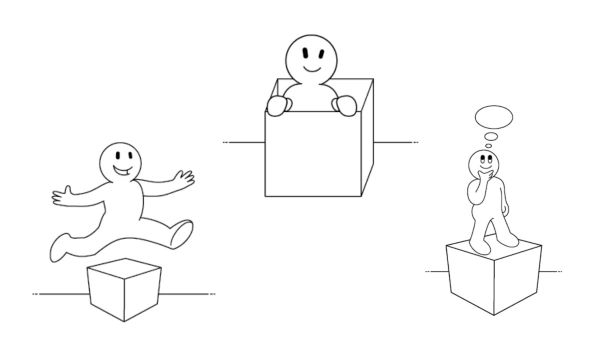

Loose Parts are just objects, what is essential is the actions that children create as they are in control of the objects. The unscripted nature of Loose Parts gives children the ability to engage their strengths and capacities to creatively utilize the objects in innovative ways. Children are natural explorers, they are constantly touching, smelling, tasting, listening, and watching the world around them. Loose Parts Play provides opportunities for children to use all of their senses as they investigate and discover the properties of the materials. When children are in control of the materials, they are more likely to be engaged in sustained and creative play.

Loose Parts play is complex and unpredictable:

Loose Parts can be found everywhere at little to no cost. The important characteristic of Loose Parts is that they are unscripted and offer endless possibilities for experimentation and play. Loose Parts play promotes creative thinking and problem solving as children experiment with the various ways they can manipulate the materials. When children are given the opportunity to freely explore and experiment with Loose Parts, they develop a sense of agency as they exercise control over their environment. Loose Parts play also provides opportunities for social interaction and collaboration as children negotiate and cooperate with each other to build and create. from an object to an action, which adds complexity to play.

Time is essential:

Children need time to explore and experiment, and a flexible schedule allows them to do just that. Loose Parts offer children endless possibilities for creative play and intellectual learning. In order to fully discover the potential of Loose Parts, children need plenty of time. A flexible schedule allows for flow and rhythm, which can further promote creativity and intellectual learning. When children are given the freedom to explore Loose Parts at their own pace, they can discover new ways to use them and develop a deeper understanding of the world around them.

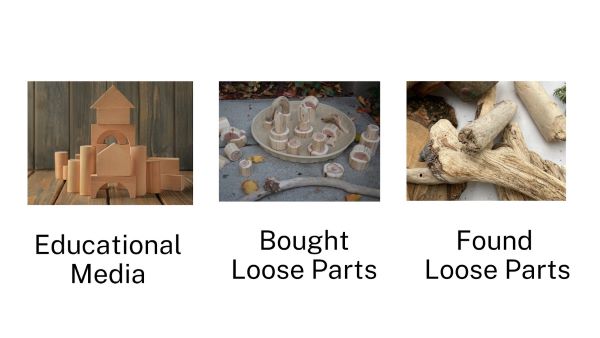

Combining and Mixing:

When Loose Parts are combined with other educational media, such as blocks, dolls, and balls, the possibilities for discovery are endless. The complexity of play increases as children combine the materials to experiment, make mistakes, and solve problems.

From creating a list of Loose Parts to Curating for affordances:

When I go on a Loose Parts scavenger hunt, I always wear an affordance lens. I never consider what children will do with the item. Instead, I think about what possibilities of discoveries the item offers children. I ask myself:

- Can the Loose Part be used to construct?

- Can it be used in art?

- Can it be used in dramatic play?

- Can it be combined with other Loose Parts or educational media?

Leave your idea outside:

While it is important for educators to provide Loose Parts for children to play with, it is even more important to step back and allow them to lead the way. Children’s ideas should always come first. We should avoid using Loose Parts to set up adult-guided ideas or activities. Instead, we should let the children take the lead and see where their imaginations take them. When we do this, we give them the gift of true play. And that is what childhood is all about.

Upcycled not Recycled:

Loose Parts are upcycled items made from a wide variety of materials. An upcycled item is different than a recycled one. Upcycling involves reusing an object for a new innovative purpose. For example, turning a wooden plate holder display into a weaving loom, a cardboard box into a house, or using a muffin tin to sort and organize beads. Recycling involves changing or treating items such as old paper, glass, cans, or plastic and turning them into new products so that they can be used again.

Invitations to Play:

When incorporating Loose Parts into the early childhood ecosystem, it is important to create an invitation to play. This can be done by placing a variety of Loose Parts in an inviting space. As children respond to the invitation, then adults can consider how to continue to provoke their interest and thinking.

Children learn most readily and easily in an environment where they can joyfully investigate and discover things for themselves. They need unscripted and unpredictable materials and opportunities to shape the environments where they play. Designing Loose Parts ecosystems bring joy and playfulness to children and adults alike.

I invite you to step back and reconsider the purpose of Loose Parts and how you will use them to design early childhood ecosystems that inspire play.

References

Hawkins, Frances Pockman (1974). The logic of action: young children at work. Pantheon Books.

Nutbrown, Cathy (2011). Threads of Thinking: Schemas and Young Children’s Learning. SAGE.

Swann, Annette C. (2008). Children, Objects, and Relations: Constructivist Foundations in the Reggio Emilia Approach. Studies in Art Education, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 36-50. National Art Education Association.