In this how-to guide, you’ll discover a process for designing and creating highly effective play invitations that include:

- The true definition of a play invitation (vs. a pretty Pinterest spread) and why it matters

- The 4 key principles that guide and shape effective play invitations

- The foundational understanding every educator must have in order to powerfully facilitate learning through play

- The 4-stage design process that ensures engaging and highly effective play invitations

Introduction

Take a quick glance at Pinterest, and it may seem like there’s a “recipe” for creating play invitations. You may see all the ingredients, and think that all you need to do is gather and arrange them, just like a cooking recipe promises a predetermined outcome from a set of ingredients prepared a certain way.

There is NO recipe for play invitations, though. In fact, designing play invitations is more like learning an art form.

A story from Sally Haughey, Wunderled Founder:

I remember when I first learned to throw clay on the potter’s wheel. Professor Manhart went through each stage of the process, painstakingly giving me over 20 important phases to be aware of when creating a beautiful pot or vase. I took in-depth notes and studied his method for days before I actually approached the potter’s wheel for the first time.

I will never forget sitting down to throw that first pot. It was an utter failure. The next 19 tries were, too. I would go to the potter’s wheel and apply what Professor Manhart had taught me. And the outcome would look nothing like I’d planned – over and over, again and again. But each time I took notes on what did work and what went wrong.

Somewhere around my 21st try… I started to find my way. I could feel the clay and move it with intention and skill. But it took a lot of practice and doing the work of not just getting the knowledge, but developing the SKILL of working with clay on the potter’s wheel.

No one sits down at a potter’s wheel for the first time and throws a beautiful vase, with no prior experience. It is a process. It takes time.

And the way to gain real skill is to be willing to fail and to keep trying as many times as it takes. Designing play invitations is no different.

What is a Play Invitation?

Let’s start by exploring what we mean by play invitations. There has been so much confusion about the definition. Is a play invitation the same as a provocation? Is a provocation a play proposal? Just try researching it online to see if you gain clarity! Confusion is all but certain.

If you’ve struggled over the terms, you’re not alone. Recently, a search for the definitions of the words invitation, provocation, proposal, and prompt yielded quite a bit of opportunity for reflection.

For our purposes here, let’s use INVITATION since it seems to make the most sense for the practitioner. When you design a play invitation – you’re designing it to invite children deeper into their play.

That invitation can provoke. It can prompt. It can be a proposal to poke at their theories. Invitation encompasses it all.

A play invitation invites you to enter into play.

A play invitation can be a simple idea, question, or action that helps the children move more deeply into their big ideas and theories.

A play invitation can be a bridge that helps make visible that there is more to be explored – something they have not yet seen.

The process of designing play invitations occurs inside the everyday work of the educator. It is a process of facilitation.

To facilitate is defined as to help forward an action or process, to assist the progress of a person. We are facilitating more complex and rich play. We introduce new language and materials to provoke deeper thinking.

At the heart of everything are relationships. We are cultivating relationships through ideas, questions, and actions in play. Relationships between ideas and theories, actions and impact, and more.

All of this is what we mean by the term “play invitations.”

Play Invitation Principles

Next, let’s cover the fundamental principles that everything else in this how-to guide is built upon. These principles are woven into the heart of every play invitation.

Principle #1: Young children have the right to play. It is how they learn.

The design process of a play invitation is based on the fact that children learn best through play. We do not think of children as empty containers waiting for our installation of knowledge. We do not view children as having “needs” in play. We see it as their right.

Principle #2: We are co-learners beside the children.

This is an essential principle. As you will see in the first two stages of the design process, we are literally learning beside the children. We come to children’s play with a beginner’s mind. We make no assumptions that we understand what we are observing in play. We are deeply interested in children’s intentions in play. As teacher researchers, we are always learning about how children learn.

Principle #3: We see, hear, and value children through the play invitation process.

To facilitate a child’s play through invitations is to see, hear and value that child on the deepest level. This is one of the most important intentions of designing play invitations. It is the way we can translate the idea of taking children into consideration. The learning process is something we do with them and not for them.

Principle #4: Children are already motivated to learn through play – it is our task to facilitate and support it.

We do not need to coax and trick children into learning. In fact, as practitioners of play invitations, we are harnessing the children’s deepest motivations in play. When we design play invitations – we understand they will be fueled not by our own agenda, but by children’s natural approach to the world.

The Foundation

What is the foundational understanding we must have for creating highly effective invitations?

PLAY!

Play is a process. An individual process. The mighty truth about play is this: Children in play are in control of the content and intent of their play.

Our role is to support those sets of behaviors. We are not here to shape, guide or direct their play – we are here to SUPPORT IT!

How do we do that? When children are in play – our role is to observe and witness. We should intervene as little as possible.

Our role is to support and facilitate the work of the children. Not suggest ideas, endlessly question children, or try to guide their thinking, but rather to keep what is already unfolding highly engaging.

Play that we structure is not true play. It is a structured play.

Play that we guide is not true play. It is guided play.

What we do is facilitate play. We get up underneath the children’s play urges and big ideas and support their motivations and intentions.

Begin by memorizing the definition of play below. Write about it in your journal. Take each aspect and really research what it means, what it looks like, and what it feels like when children are deep in true play.

This is your compass for setting up invitations and provocations. This is the launching point.

“Play is a set of behaviors that are freely chosen, personally directed, and intrinsically motivated.”

Penny Wilson, The Playwork Primer, 2010 Edition

How can we facilitate freely chosen?

How can we facilitate personally directed?

How can we facilitate intrinsically motivated?

The process of designing play invitations is an art form just like working with clay. Let’s unpack the design process so that you can create your own art through your teaching practice, just as Sally learned to create pottery she could be proud of.

The Design Process

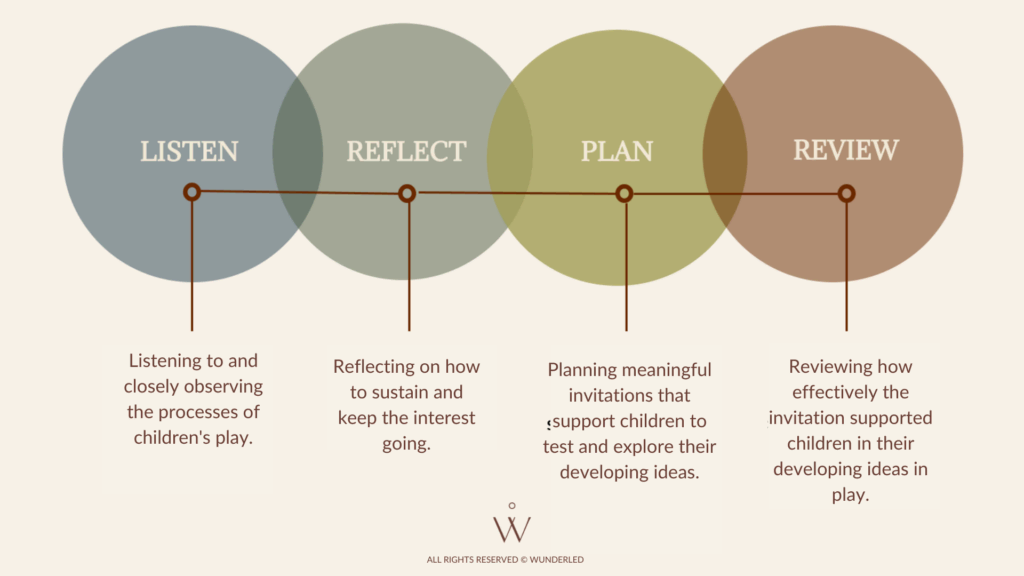

There are four distinct phases characterizing a design process that leads to highly effective, engaging play invitations.

Phase 1: LISTEN

Listening to and closely observing the processes of children’s play.

Phase 2: REFLECT

Reflecting to understand and identify children’s motivations, and how to sustain, and keep the interest going.

Phase 3: PLAN

Planning meaningful invitations that support children to test and explore their developing ideas.

Phase 4: REVIEW

Reviewing how effectively the invitation supported children in their developing ideas in play.

We’ll cover each of these stages in depth below.

Phase 1: LISTEN

The Listening Process is a search for intention.

INTENTION is defined as A thing intended; an aim or a plan. When we listen for a child’s intention, we are listening for their personal aim or plan.

It is important to take time to really understand what’s at the core of the children’s interests and intentions.

To listen is to welcome what happens at the moment. It reflects true respect for children’s play.

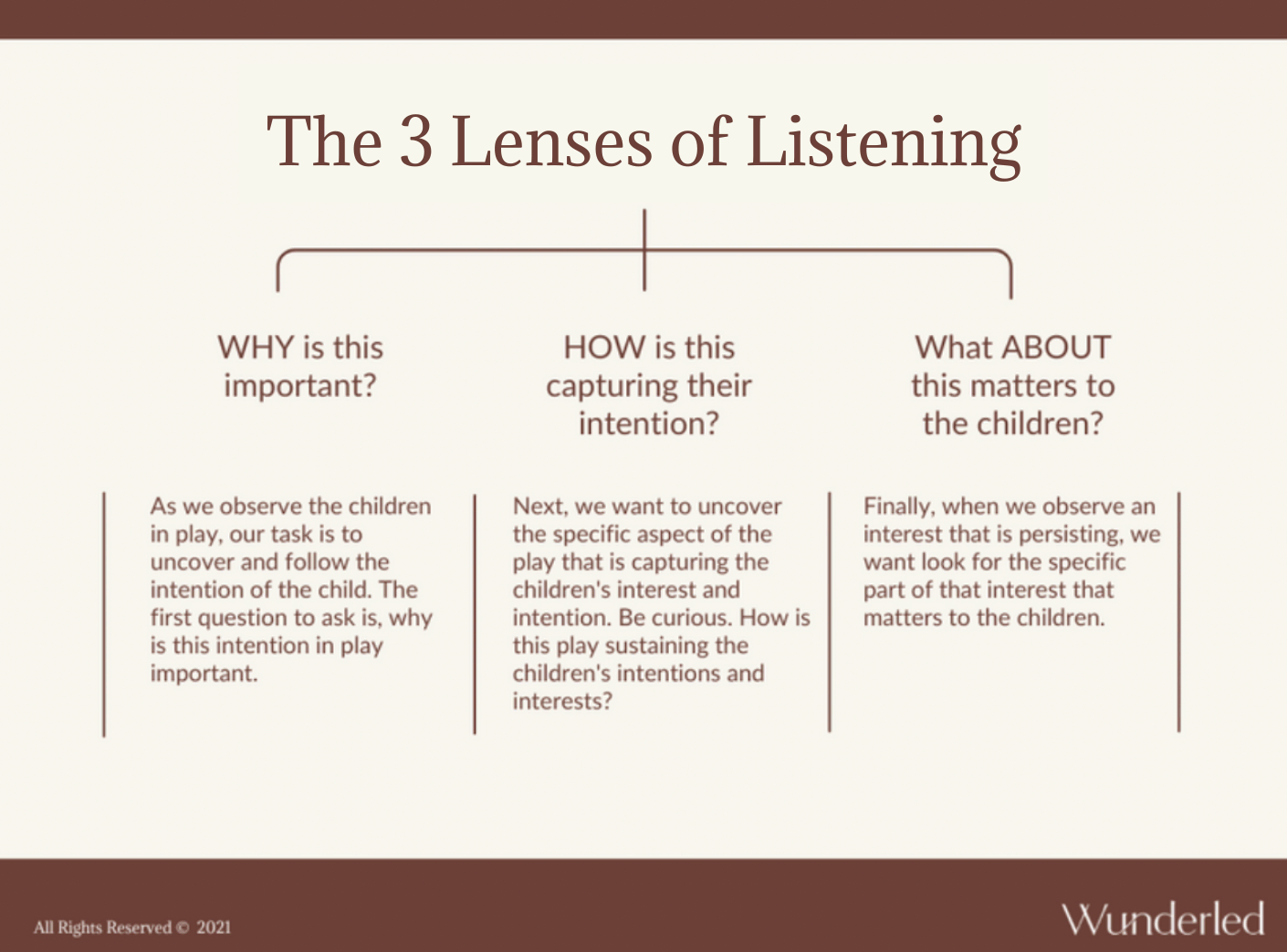

To begin, let’s look at what we call the 3 Lenses of Listening. The 3 Lenses of Listening give you a cognitive filter for listening to children’s play.

Children have many interests. Our task is to sort through the many things that interest children and to find the things that hold possibilities for exploration. When we see one that is rich, it is time to lean into the children’s intention – to discover why it is meaningful for them.

The 3 Listening Lenses help us explore the meaning and function of play for children.

From these inquiries, we can design questions or invitations to uncover what is needed to help extend and deepen the children’s play ideas and theories.

Lens 1: WHY is this important?

As we observe the children in play, our task is to uncover and follow the intention of the child. The first question to ask is, “Why is this intention in play important to the child?”

Through this first lens, we aim to uncover, find and follow the intention of the child. We examine the children’s intentions.

It takes time to really understand what’s at the core of the children’s interest and intention. We listen for something that is important. (Not from an adult perspective but in the child’s view.)

Lens 2: HOW is it capturing their intention?

Next, we want to uncover the specific aspect of the play that is capturing the children’s interest and intention. Be curious. How is this play sustaining the children’s intentions and interests? What makes up the play that is happening?

This is where our understanding of play becomes super important. Is it a play urge or pattern that is engaging and sustaining the children’s play? Is it the social dynamic or the ideas and theories they are exploring?

Lens 3: WHAT about this matters to the children?

Finally, when we observe an interest that is persisting, we want to look for the specific part of that interest that matters to the children. What is the child connecting to throughout that play?

In lens #2 we look more at the ways play engages children. Here, in lens #3 we are looking for the children’s perspective.

Why does it matter to them? We tune our listening for what the children care deeply about in their play. What theories, ideas, and actions is the child exploring?

A note on listening: Listening is the first of the 4 stages of designing play invitations, and is crucial to success with play-based learning because it provides a strong foundation for each of the other phases of the process.

A highly effective play invitation depends upon our ability to understand what we are seeing. We cannot assume we know what we are observing in play – because what we know is influenced by our past experiences.

Instead, we must become careful listeners to support the process of play. By doing so, we are supporting how children process and work through theories, ideas, and projects.

Phase 2: REFLECT

In the Listen stage we gather the data – be it photographic, video, and/or narrative. In the Reflect Stage, we reflect on what we have gathered and look for those golden threads of children’s motivations and interests.

We begin looking at the ways we witnessed the children play. We begin to connect the dots between play urges, play ideas, and the social relationships emerging.

Reflective practice is a daily, continuous process. Donald Schon, in his book The Reflective Practitioner, introduced the ideas of “reflection-in-action” (thinking on your feet) and “reflection-on-action” (thinking after the event). Here, we are going to focus on the latter.

To design highly effective play invitations, we want to do some reflection-on-action (again – thinking after the event), looking at four perspectives:

The Physical – Play Urges and Schemas

The Emotions – Play Engagement/Interests

The Social – Social Relationships

The Cognitive – Play Intentions

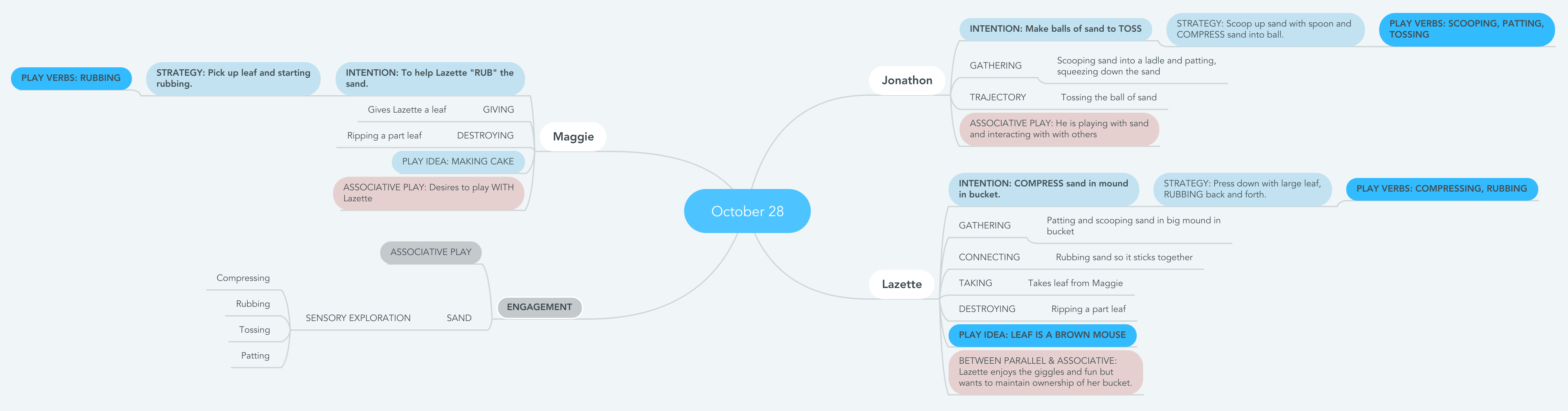

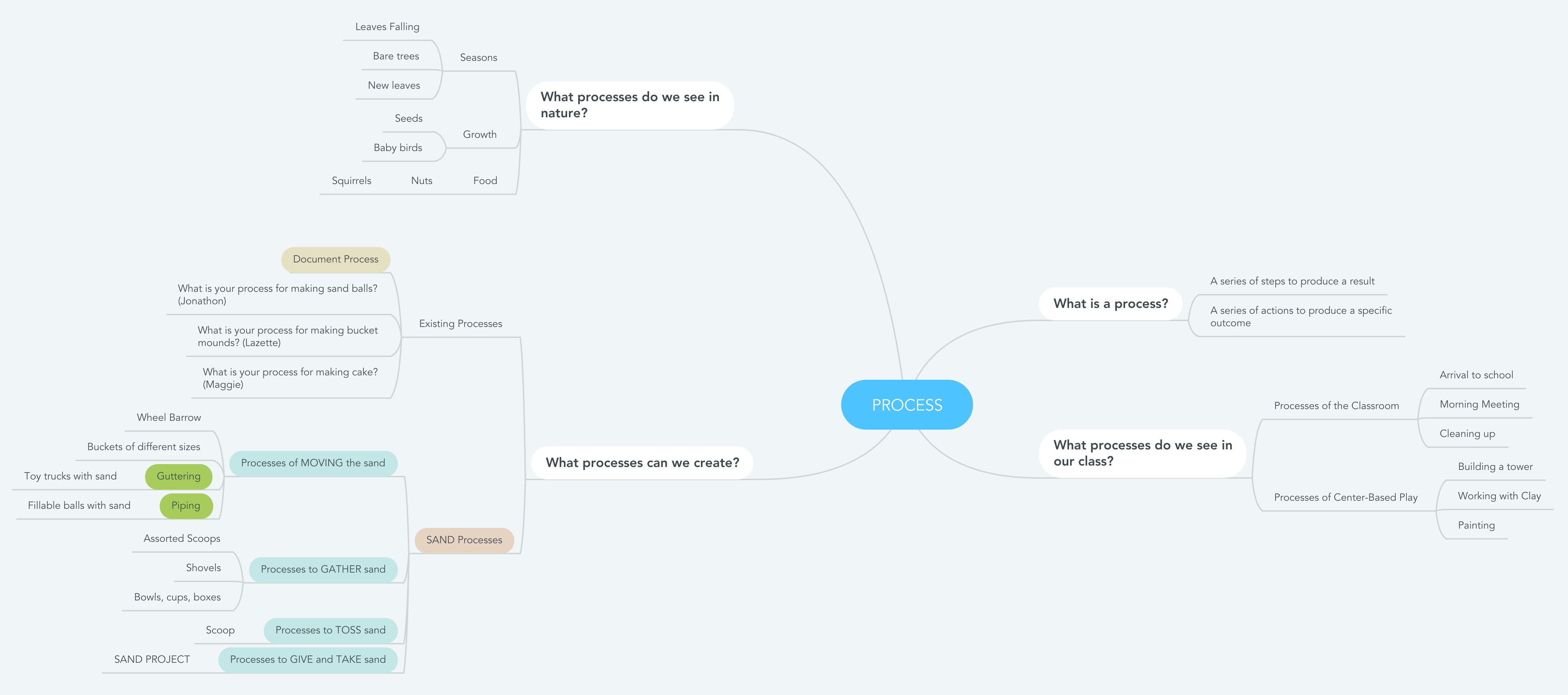

To help organize my observations I love to use a min map and I call that process: Play Mapping Process.

Play Mapping Process

Play mapping is basically mind-mapping what we see in play. Despite the proliferation of electronic tools available – try beginning with pencil and paper. It allows you to crumple the paper and start again.

Click here to see this observation mind map of children play bigger.

Once the process becomes second nature, move to use software such as MindMeister. (The maps shown here were created on MindMeister.)

Play mapping will put you in the mindset of a researcher or detective. It places all of the mini-moments of play as pure data. You can map exactly what you gathered without imposing assumptions.

A bonus: parents and administrators often LOVE the clarity offered by play mapping. It gives real weight and makes visible all of the layers of understanding and expertise we bring to our work.

Phase 3: PLAN

At this stage, we are looking at our observations and play mapping for threads of inquiry, and designing a play invitation that supports the natural inquiry process of children and builds on their interests.

Step 1: Identify Threads of Intention

This is where all of your observations come in and help you home in on what matters! Children’s curiosity leads to action, which is their research. We want to zero in on their research.

Questions to ask include:

What is pulling these children to keep returning to this play?

What fascinates them about this particular play urge or big idea?

What matters most about this play?

Step 2: Select an Overarching Big Idea

The next step is to find the overarching idea that will harness the inquiry of all the children involved. What connects them? Sometimes it is clear. Questions to ask include:

What concepts connect to this play?

What big idea holds rich possibilities for new materials and experiences?

What concepts move past existing play?

You can also reflect on a big idea for each child. Go to a thesaurus with each of the big ideas you see as a possibility. Then, reflect on each of the concepts or big ideas you have selected and relate it to the children’s research that you observed.

Looking at these – which ones have the most possibilities that spring forth from the children’s current interests and play intentions?

Step 3: Create a Web of Possibilities

In this step, you want to ask:

What are all the possible ideas that can be explored through this big idea?

What questions of wonder are possible?

This is a game-changer. It has the potential of taking a 2-minute play episode and building a web of possibilities that could last a year.

That’s powerful and what you could call FORWARD PLANNING. This web will be your play invitation roadmap.

Click here to see this web of possibilities bigger.

The web you see here was created on MindMeister, just like the play map. The key big idea is placed in the middle and there are several questions (come up with at least 3) that can lead to conversations and inquiries.

One question is always about What does the concept mean? What’s so great about this, is that it brings the possibilities to other areas of the children’s lives so that the concept can expand and grow with the children’s expanding interest.

It gives you places to make connections as you see here. Hopefully, you’re seeing that there is massive potential for learning when we use a big idea vs. a topic or theme. It literally allows for hundreds of new play invitations.

You have no idea what will ignite the children’s interest. Maybe you will notice the fall leaves and have a conversation where you wonder with the children about the process of falling leaves – and perhaps that sets the sails of play in a whole new direction, while still remaining connected to prior experience.

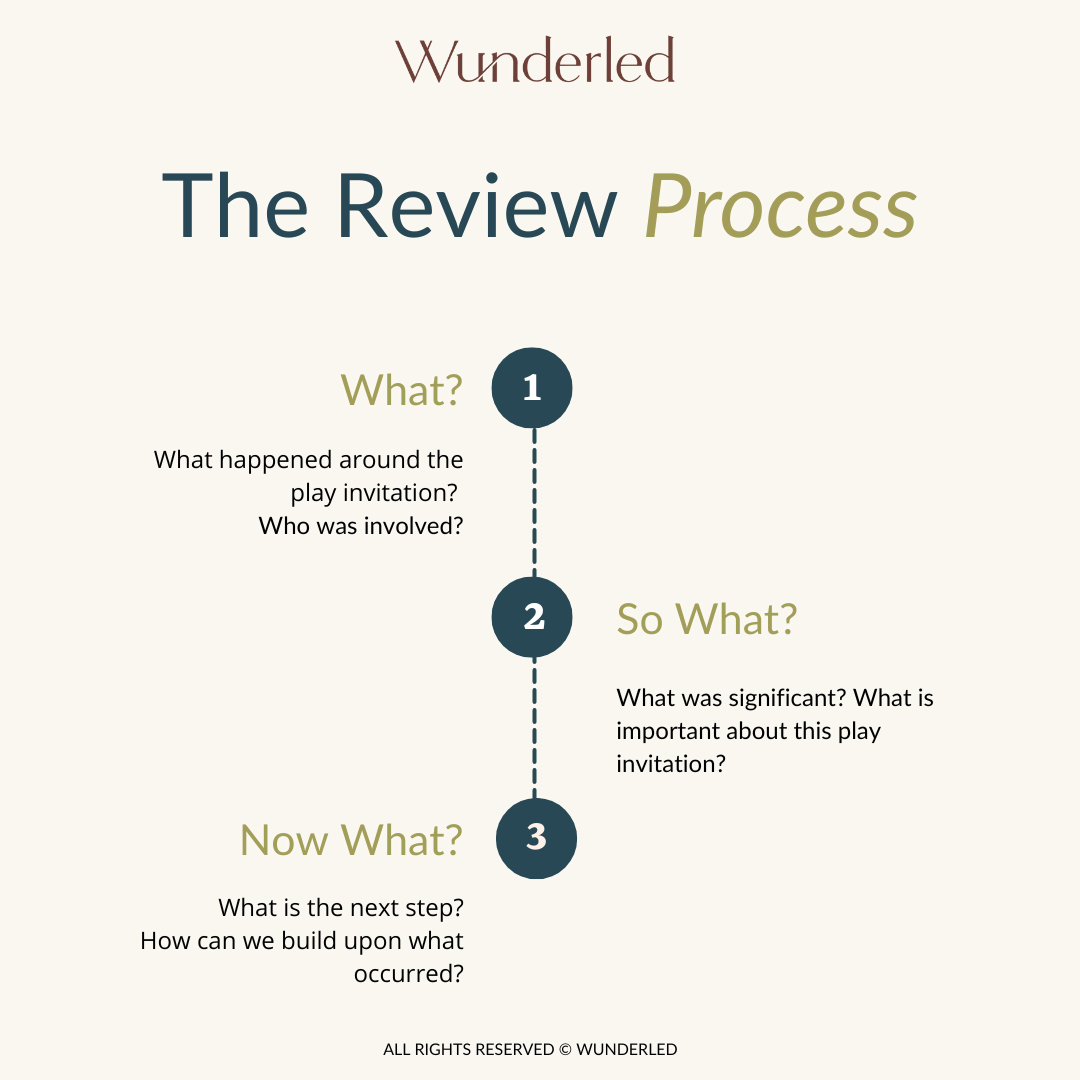

Phase 4: REVIEW

The power of the process of designing play invitations comes from the important stage of review and reflection.

“We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.“

John Dewey

This process empowers you to gain self-awareness and become highly effective in facilitating and supporting play. This is where the process of being a co-learner becomes a living truth.

Reach, Touch and Teach was published in 1970 by an American school teacher, Terry Borton. In his book, he developed a What, So What, Now What sequence of reflective education that also acts as a framework for reflective practice.

What?

Noticing – The Description Stage Of the Review Process

What happened around the play invitation? Who was involved?

This is the stage of noticing. It is reviewing what happened, objectively. Without judgment or interpretation. It is looking at what happened in detail the facts and event(s) of the play invitation experience.

So What?

Processing – The Knowledge Building Stage of the Review Process

What was significant? What is important about this play invitation?

This is where we process what happened. We gain understanding from what we learned. We look deep at the WHAT behind the experience of the play invitation. At this stage we review our own feelings, ideas, and analysis of the play experience.

Now What?

Plan of Action – The Action Stage of the Review Process

What is the next step? How can we build upon what occurred?

This is the level of synthesis – where we build on the previous levels of understanding to consider what we are going to do next. Here we consider the broader implications of the play invitation experience and apply learning.

The review process is where you learn and deepen your understanding of play. It is a crucial step to building confidence as an educator.

Conclusion

In conclusion, creating highly effective invitations to play is an art that requires thoughtful listening and planning, attention to detail, and a deep understanding of children’s development and interests. By following the steps outlined in this post, you can create a variety of engaging and meaningful play experiences that support children’s learning and development. Remember to be flexible and open-minded, and to allow children to take the lead in their own learning journey. With your guidance and support, they will develop the skills and confidence they need to thrive in the world around them.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out our latest post with 23 ways to use Loose Parts play for academic learning.

Excited to put this process into action? Awesome! We have curated a collection of inspiring play invitation ideas free for you to use. Let the fun and learning begin!

Have you tried mind mapping before?

What is your biggest road block when designing play invitations?

References

Curtis, Deb (2004). Creating Invitations for Learning. Child Care Information Exchange.

Copple, Carol; Bredekamp, Sue (Eds) (2008). Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8. The National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Murdoch, Kath (2015). The Power of Inquiry: Teaching and Learning with Curiosity, Creativity and Purpose in the Contemporary Classroom. Seastar Education.